A Tainted Inheritance

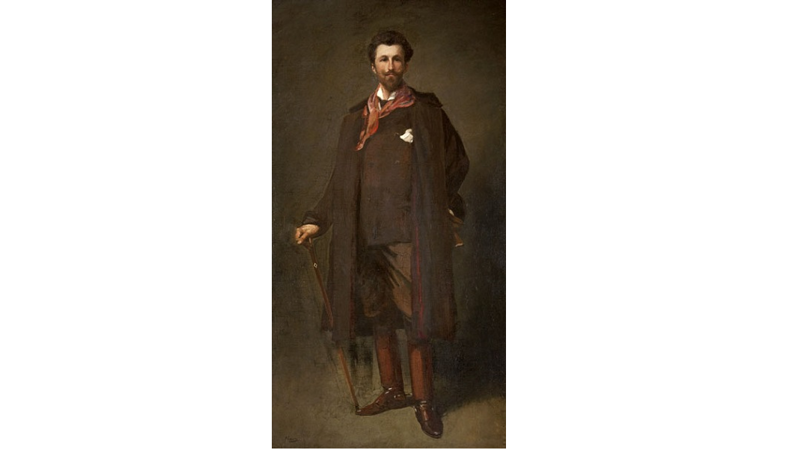

RB Cunninghame Graham by Sir John Lavery

1181

Images © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

14th June 2023

The wealth generated by transatlantic slavery was not enjoyed solely by the individuals who owned plantations in the Caribbean and forced enslaved people from Africa to work on them. Their descendants benefitted too, through inheritance of money, vast estates and social status which gave opportunities to later generations in Scotland. These opportunities – based on wealth derived from enforced labour sometimes hundreds of years before – were not afforded to the families or descendants of the enslaved people themselves.

One person to benefit in this way was the eccentric Scottish socialist politician, writer, cattle rancher and adventurer Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham (1852–1936). A romantic figure with a Spanish heritage, he was brought up on and inherited his family estate of Gartmore in Stirlingshire. He travelled extensively in South America, where he was known as ‘Don Roberto’. He wrote about his travel experiences and the history of the countries he visited, and also published Scottish stories and biographies. An excellent horseman, during World War I he purchased horses for the British Government in South America. He was a Liberal Party MP and a founder and first president of both the Scottish Labour Party and National Party of Scotland.

Cunninghame Graham was able to travel and become involved in politics at least in part due to the wealth and status of his family, who owned three large country estates in Scotland – as well as Gartmore, Finlaystone in Renfrewshire (now in the local authority area of Inverclyde) and Ardoch in Dunbartonshire (now in the West Dunbartonshire). The family properties had been expanded and improved by his great-great-grandfather, Robert Graham of Gartmore (1735–97), who made a fortune through his involvement in transatlantic slavery and ownership of Roaring Hill and Lucky Hill sugar plantations in Jamaica, which were worked by enslaved people from Africa. Robert Graham even brought two enslaved Africans back to work for him in Scotland. His money and estates were passed on to his children, grandchildren and in time to Cunninghame Graham. Although Cunninghame Graham’s father had left significant debts when he died in 1883, the sale of Finlaystone and Gartmore estates in 1901 allowed Cunninghame Graham to pay off his creditors and continue to live a privileged existence on his Ardoch estate.

Cunninghame Graham wrote a biography of Robert Graham, Doughty Deeds, in which he openly discussed his ancestor’s role in buying and selling enslaved Africans and the ways they were mistreated on the plantations. As someone who fought against the iniquities of colonialism and the imperialist attitudes of his time, it was troubling for Cunninghame Graham to confront his family’s past. He sought to understand how his ancestor had willingly participated in a practice that he had claimed to object to: ‘All through his life Robert Graham held firmly to the Liberal politics of his family. In several of his letters from Jamaica, he laments having to pass his life in a land of slavery. At the same time he was a slave-owner, but not feeling in the least impelled to sell all that he had’. Cunninghame Graham concluded that in the eighteenth century the system of slavery was so embedded in British culture that to act against it was extremely difficult. He explained this in a passage – written in 1925 – which also demonstrates that, despite the legal abolition of slavery, the racist attitudes of slavery still persisted in the governance of the British Empire in the twentieth century:

‘Slavery then was recognised by law. Cabinet Ministers, the nobility and high-born ladies all were actual or potential slave owners. To doubt the justice of the institution would have caused a man to be dubbed a crank, just as it would to-day if, in a British colony, someone insisted that a white citizen should be hanged for murdering a black.’

Cunninghame Graham was a strong anti-imperialist and campaigner for social justice and did not seek to excuse his ancestor’s exploitation of enslaved people. However, his explanation that slavery was the accepted norm is weak and fails to acknowledge the strong anti-slavery movement that grew in the late eighteenth century. Unlike many liberals, Robert Graham was not an abolitionist and instead he continued to own and profit from enslaved people long after he returned to Scotland.

Brian Weightman,

Learning Assistant, Glasgow Museums

Find out more about Robert Graham and Gartmore: