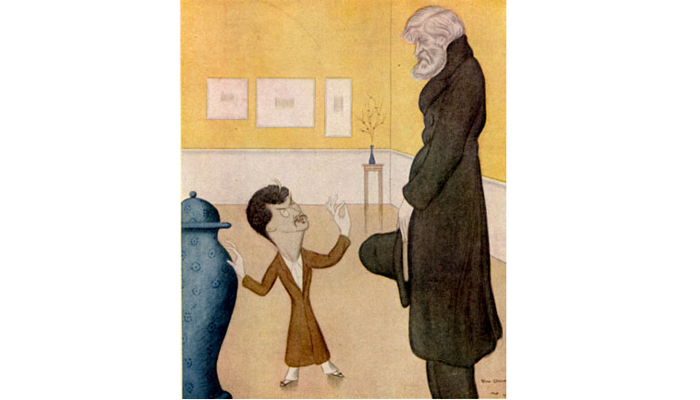

Arrangement in Racism and Black Injustice: Whistler’s Colour Theory

James McNeill Whistler, Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 2: Portrait of Thomas Carlyle, c.1873–74

671

Image © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

2nd December 2020

In 1873–74 James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) painted the portrait of Scottish historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881). Like Carlyle, Whistler was a confrontational figure, known for his defiant and acerbic temperament, who took on the art establishment in his provocative declarations and radically pared-down compositional arrangements. Challenging the very nature of portraiture, he claimed that colour harmony and pictorial balance were more important that the identity of the sitter, provocative indeed when painting such a renowned Victorian sage.

Whistler admired Carlyle. He quoted from Carlyle in his letters and frequently styled his writings on the language and rhetoric of the Old Testament prophets in the manner of Carlyle to give his arguments satirical weight. He did not share Carlyle’s sympathy for the British working poor, opposing the British Museum opening on Sundays for fear that ‘the working man drop the sweat of his brow upon the Elgin Marbles’. And he certainly didn’t agree with Carlyle’s extolling of the virtues of work. Whistler wrote: ‘To say of a picture, as is often said in its praise, that it shows great and earnest labour, is to say that it is incomplete and unfit for view.’ However, Whistler did agree with Carlyle when it came to matters of race.

Images

Carlyle expressed appalling views on slavery and people of colour in his ‘Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question’ (1849), views that were applauded by Americans in the pro-slavery south. Whistler’s younger brother Dr William McNeill Whistler (1836–1900) served as an assistant surgeon with the Confederate army during the American Civil War. His great uncle Zephaniah Kingsley Jr. (1765–1843) was a slave trader and plantation owner in Florida who took four enslaved African wives; the first, Anna Madgigine Jai, was only 13 when he bought and married her. Whistler’s letters are littered with racist language. In 1867 he was expelled from the Burlington Club in London after a string of assaults, including an attack on a black passenger on the steamer Shannon in 1866 on Whistler’s return voyage from Valparaiso, Chile, where he had gone on a gun-running expedition, persuaded by former Confederacy men in London. Whistler wrote to the Director of the National Gallery, William Boxall (1800–1879), on 24 December 1867: ‘This “passenger” was simply a Negro, among several forced upon our company on board. – The degree to which he offended my prejudices as a Southerner who for the first time found Negros at the same table, led finally to our coming into collision […] the black scoundrel deserved his kicking’. The assault was so fierce it left Whistler’s right hand ‘utterly maimed and disabled’. Despite his injury, the next day Whistler came to blows with Captain Baldwin Arden Wake (1813–1880), an abolitionist who dared criticise his behaviour.

Reflecting on his painting of Carlyle, Whistler wrote in 1891: ‘He is a favorite of mine – I like the gentle sadness about him! perhaps he was even sensitive – and even misunderstood – who knows!’ The painting was exhibited at the International Exhibition in Glasgow in 1888 and following a campaign by leading Scottish artists it was purchased by the by the city of Glasgow in 1891, making it the first ever Whistler painting to enter a public collection.

Considered purely as a work of art, Whistler’s portrait of Carlyle is a masterpiece of aesthetic arrangement and tonal harmony and a coup for the city which was to become the centre for Whistler scholarship with gifts from the artist’s sister-in-law Rosalind Birnie Philip (1873–1958) to the University of Glasgow in 1935, 1954 and 1958. However, dialogue around this painting, whose very title positions itself in terms of colour, needs to acknowledge the noxious prejudice and racism of both artist and sitter.

Dr Jo Meacock,

Curator of British Art