Cecilia Douglas – Art Collector and Owner of Enslaved People

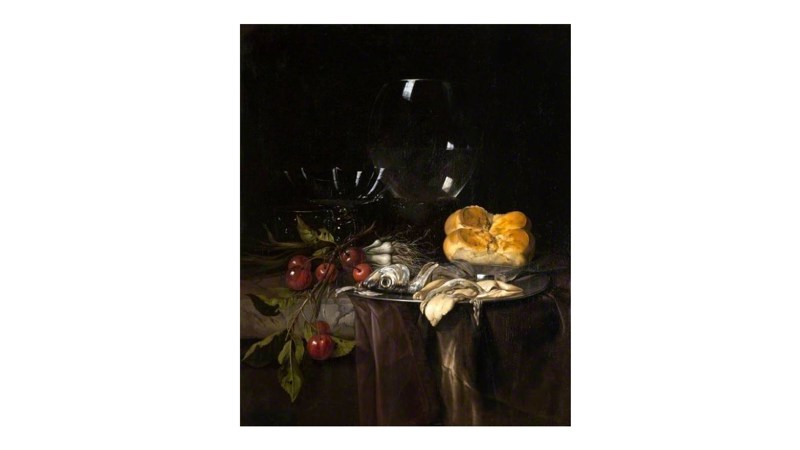

Still Life: Herring, Cherries and Glassware, Willem van Aelst, 1680; one of the oil paintings bequeathed by Mrs Cecilia Douglas, 1862

307

Images © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

3rd November 2021

In 1862 Mrs Cecilia Douglas (nee Douglas) bequeathed oil paintings and sculptures to the then Glasgow Corporation. The paintings initially were on display in the Corporation Art Galleries in Sauchiehall Street before being moved to Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum. Most are now in store at Glasgow Museum Resource Centre.

She and her husband Gilbert married in 1794 and came from two different branches of the Douglas family. Hers apparently was descended from the Douglas Earls of Angus, Gilbert’s from the Douglas’s of Mulderg in Ross-Shire. Her mother was Cecilia Buchanan daughter of maltman George Buchanan of Glasgow.

Both Douglas families and the Buchanans were well to do with a lineage going back to the 15th/16th centuries. Consequentially they were well placed financially when the Act of Union in 1707 opened up the American Colonies to legal trade by Scottish merchants. By 1730 George Buchanan’s brothers were Glasgow’s largest tobacco importers, his younger brother Archibald being the son in law of Alexander Speirs.

The Douglas families, much later, were involved in the sugar and tobacco trade husband Gilbert owning plantations in St Vincent and Demerara, British Guiana, and Cecilia’s brothers individually or through their company J. T. & A. Douglas & Co owning (or as mortgagees) at least six plantations in British Guiana, with two of her brothers living there and owning enslaved people.

When slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1834 they claimed compensation, receiving as owners £41,517 and a further £48,874 from other owners which paid off their outstanding mortgage debt. That sum was in addition to the profits they made over the lifetime of the company, the majority of that time investing in human misery to their clear advantage. That misery erupted into a rebellion in Demerara in 1823 which was savagely put down by the military with hundreds of enslaved Africans killed, those who weren’t being sentenced to 1,000 lashes and hard labour.

When Gilbert died in 1807 he bequeathed half shares in his plantations to Cecilia. As it turned out the plantations had debts which Cecilia paid off by continuing to sell the Demerara produce for a time and eventually her half share in the plantation itself.

The Death of Julius Caesar, Vincenzo Camuccini, circa 1825-1829; one of the oil paintings bequeathed by Mrs Cecilia Douglas, 1862

318

Images © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

She had a number of significant industrial and financial investments which included the Forth and Clyde Canal, the Bank of England and various railway stocks. She also retained her half share in the ownership of the St. Vincent plantation which had 231 enslaved Africans. When slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1834 she claimed compensation and in 1836 was duly awarded £3,014. When she died in 1862 her estate was valued at £40,365 (approximately £5 million in today’s money). As well as the artworks she bequeathed considerable amounts to poor relief and medical charities, but the majority of her wealth was redistributed among her extended family.

In 2013, articles about her bequest appeared in the Herald newspaper, one entitled ‘The Paintings Sullied by Slavery’. It goes into detail about the Cecilia Douglas fortune being founded on slavery and asks the inevitable question about whether paintings with their financial provenance should ever go on show. A complex question with no easy answer. The following are two telling and moving extracts referring to the conditions on the Douglas plantation in St. Vincent.

“Slavery conditions on the Mount Pleasant estate on St. Vincent were brutal. Large gangs of slaves would spend much of the day digging holes for the sugar cane and constantly weeding the plantation, with women not spared such physical labour.”

“The slaves die off because they are being worked in very difficult conditions very hard with inadequate nutrition.”

It’s clear that the wealth of Cecilia Douglas and her husband came about, either directly or indirectly through the exploitation of enslaved Africans, the quotes above indicating what little regard they had for the enslaved people creating their fortunes.

George Manzor,

Volunteer Researcher at Glasgow Museums