Glasgow and the campaign to end slavery

William Smeal, the Recording Secretary and Treasurer of the Glasgow Emancipation Society

PP.1982.227.45

Images © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

5th October 2022

In 1833 the UK Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act, which outlawed slavery throughout the British Empire, although it did not fully take effect until 1838. However, Britain’s involvement with slavery did not end there. The legislation excluded territory administered by the East India Company, rather than the Crown, so millions of Indians remained enslaved. British merchants remained free to trade with countries outside the Empire where slavery still existed. Britain also continued to finance and equip the transatlantic slave trade. British capital funded businesses which relied upon enslaved labour, from Cuban sugar plantations to gold mines in Brazil. British shipyards continued to build ships used for transporting enslaved people.

Although relatively small numbers of enslaved people had passed through Scotland’s ports, many wealthy Scots had made fortunes by investing in the slave trade and in the plantations where enslaved people were forced to work. Others grew rich through importing tobacco, sugar, cotton and rum produced on American and Caribbean plantations. Glasgow’s mercantile elite generated so much wealth this way that they were known as ‘tobacco lords’. The Industrial Revolution received a boost as their profits were invested in coal mines, factories and shipyards, transforming Glasgow into the ‘workshop of the world’.

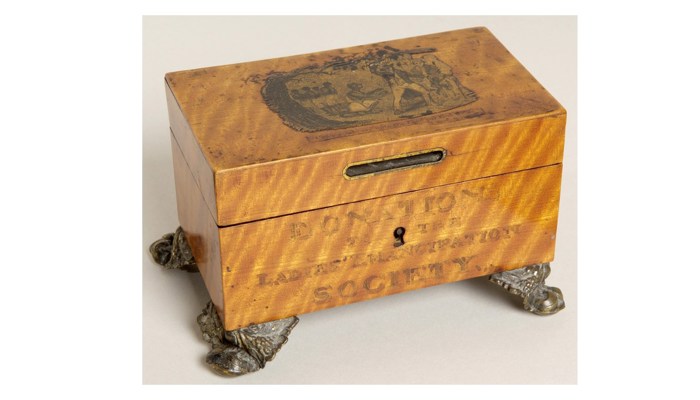

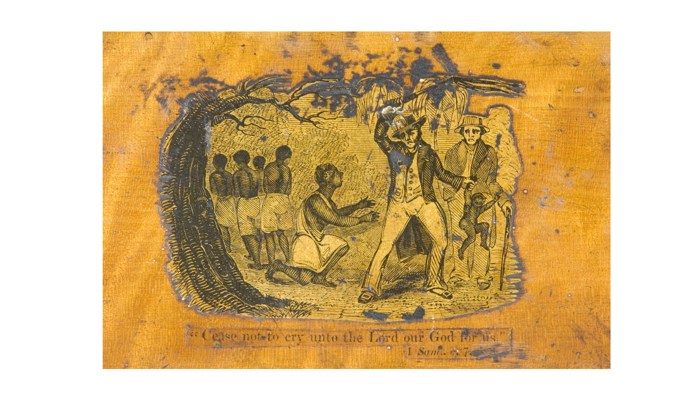

Meanwhile, British campaigners continued to fight for an end to slavery worldwide. Scottish campaigners were prominent in the struggle. The Glasgow Anti-Slavery Society, which later became the Glasgow Emancipation Society, was founded in 1822 by William Smeal, a Quaker grocer and tea merchant. Many women played an active role in the campaign. They were sometimes prevented from fully participating in male dominated organisations, so they established their own, entirely independent, bodies. William Smeal’s sister Jane Wigham (née Smeal) was the founder and leader of the Glasgow Ladies’ Emancipation Society.

Images

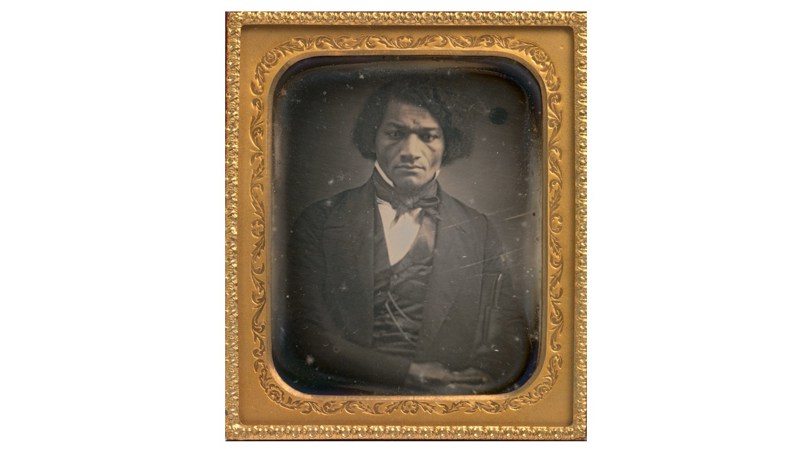

In 1846 William Smeal invited the anti-slavery campaigner Frederick Douglass to come to Glasgow. Douglass was a superstar of the American abolition movement. Born in Maryland, USA, around February 1818, his mother was an African American enslaved woman, while his father was white and possibly her enslaver. He was taken from his mother and, from the age of six, sent to other households where he was held and compelled to work, and where he secretly learned to read and write. In 1838 he escaped to New York City. After telling his story at an abolition meeting, he became an anti-slavery lecturer. In 1845 he published a bestselling autobiography. In the same year he crossed the Atlantic, and he then spent the next two years on a lecture tour of Ireland and Great Britain, his eloquence drawing many large crowds.

Frederick Douglass was one of the most photographed Americans of the 19th century.

He never smiled in photographs, to avoid his portrait being used to support racist caricatures about ‘happy slaves’. He was 27 when he arrived in Glasgow and this portrait shows him at around that age.

Image from Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. Designated as Creative Commons Zero (CC0) through the Smithsonian Open Access Initiative. Available in other formats and file sizes at https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.80.21.

Images

On Thursday 15 January 1846, some 1,500 people crowded into Glasgow’s City Hall, on Candleriggs in the Merchant City, to hear Douglass give the first of several lectures in the city. Douglass noted that the audience were ‘principally working people’, adding that ‘few learned or reverend gentlemen graced our platform’. Several years earlier, Jane Wigham had made a similar observation about the supporters of abolition, saying that ‘neither the noble, the rich, nor the learned are to be found advocating our cause. Our subscribers and most efficient members are all in the middling and working classes.’ Public lectures were an important source of information and entertainment, and Douglass did not disappoint. He was a charismatic speaker and talented mimic who could inspire both indignation and laughter. He attacked the injustice of slavery and condemned the Free Church of Scotland in particular. Their fundraisers had solicited donations from people in America who were involved with slavery, and he demanded that they ‘Send Back the Money!’

Douglass stayed with William Smeal in his home above his grocery shop at 161 Gallowgate, Glasgow. For the next three months this would be his main base as he toured Scotland, speaking from Ayr to Aberdeen. He regularly returned to collect deliveries of his autobiography, which he sold at his lectures for half a crown.

On his return to America, Douglass used funds raised on his tour to establish an abolitionist newspaper, held political appointments, supported the Underground Railroad – a network that helped people escaping slavery – and campaigned on many issues, including the right to vote for African Americans and for women. At the end of the American Civil War (1861–65) slavery was finally abolished in America. Douglass died in 1895, the most influential African American of the nineteenth century.

Alan Greenlees,

Collections Access Assistant