Patrick Colquhoun of Kelvingrove

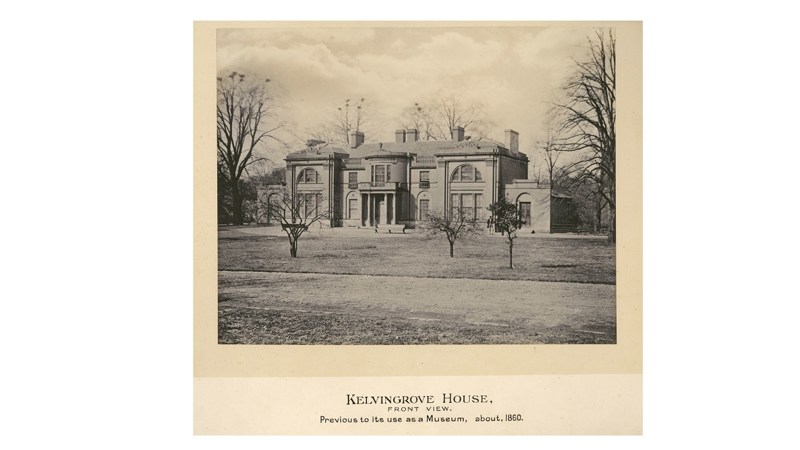

Kelvingrove House circa 1860

TEMP.3132.4

Images © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

10th March 2021

Before Kelvingrove became a public park it was a desirable private country estate located among gently rolling hills, farm land and ancient woodland.

From 1782-1790 the estate belonged to colonial merchant Patrick Colquhoun, who is thought to have built Kelvingrove House. By 1870 Colquhoun’s old mansion was refurbished into the city’s first municipal museum – the ancestor of today’s Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum.

Colquhoun has been called ‘the Father of Glasgow’ because of his role in promoting Glasgow’s trade and manufacturing during the late 1700s. In fact, he referred to himself in this way when drawing up his will in 1817. As a civic leader and merchant, he led the way in protecting the interests of Glasgow’s merchants and manufacturers. And being a Bailie (1778 and 1780) and Lord Provost of Glasgow (1782-4) put him in a powerful position to do so. He pioneered several initiatives, all of which enabled merchants and industrialists in the West of Scotland to make the most of the opportunities trade with the British colonies offered.

With fellow merchants he founded the Tontine Coffee House, home to Glasgow’s West India Club, of which Colquhoun was a member, and the place where colonial merchants would meet and do business. He founded Glasgow’s Chamber of Commerce, which existed to protect trade and manufacturing, and became its first chairman and commercial agent in London. He directed the operations of the Forth & Clyde Canal company which opened up new opportunities for merchants to ship colonial produce to the Continent and Scottish-made products to the colonies. It was these, and many other initiatives that earned him the title ‘Father of Glasgow’ and made sure he would be celebrated for centuries to come. But they divert attention away from the prerequisites of the colonial commerce Colquhoun worked all his life to promote – slavery and exploitation.

To Colquhoun, the British Empire was a vast opportunity waiting to be exploited in a multitude of ways. His own businesses traded in commodities produced by enslaved labour. During the American War of Independence, he and his business partner, the tobacco giant Alexander Speirs, supplied rebellious colonies with British and European goods. On at least one occasion one of his ships carried enslaved people from Jamaica to North Carolina.

The British Empire was also a handy recipient for society’s outcasts. During the early 1770s Colquhoun made money transporting Scottish convicts from Greenock and Glasgow to Maryland in the American colonies. As joint owner of one million acres of wilderness in the state of New York he organised the transport of German vagrants to settle there, and he prepared plans for shipping prostitutes from London to Britain’s newly acquired colony of Trinidad where they could ‘improve’ their lives.

Throughout his career Colquhoun acted in the interests of the colonial mercantile elite. In 1787, encouraged by tobacco lord William Cunninghame, Colquhoun supported merchants and planters who had incurred losses as a result of the American War. He estimated that the unpaid debts owed to them, and confiscated property including enslaved people, was worth nearly £4 million at the time.

silver tea urn

E.1966.1

In 1785 Patrick Colquhoun successfully lobbied Parliament on behalf of the cotton industry to repeal a tax on cotton goods – in gratitude of which the muslin manufacturers of Glasgow presented his wife with a large silver tea urn, now in the collection of Glasgow Museum.

In 1789 Colquhoun sold Kelvingrove and his town house in Argyle Street and relocated to London where he was appointed police magistrate. He wrote extensively on police and social reform and on the evils of crime including plundering of commercial property. His influence in London and his close relationship with Henry Dundas led the planters and those who held people in slavery in St Vincent, Nevis, Dominica and the Virgin Islands to appoint him as their agent in Britain. It was his job to carry out business at their request and ensure West Indian interests were represented at Westminster.

In 1798 London’s powerful West India merchants and absentee planters approached him for a solution to the problem of dockland crime, notably theft of their valuable West India goods from ships moored in the Thames. Colquhoun immediately drew up plans for a marine police force which were adopted within months – essentially a government-backed private police unit specifically put in place to protect the lucrative West India trade, and the forerunner of the Metropolitan Police Marine Policing Unit. As a mark of their gratitude, the West India Merchants and Planters presented him with a gold snuff box.

Back in Glasgow Patrick Colquhoun received an honorary degree from Glasgow University in 1797. In 1938 the Junior Chamber of Commerce established the annual Colquhoun Dinner. The Chamber of Commerce also raised funds to establish the Colquhoun Lectureship in Business History at the University of Glasgow in 1959. This perpetuated his reputation as an illustrious city father, but did little to explore how he made his money. It is about time we took a closer look at Colquhoun from a different perspective and consider the ways in which his wealth benefited Glasgow.

Katinka Stentoft Dalglish,

Curator of Archaeology