A Quick Beginner’s Guide to Reading 19th Century Cursive

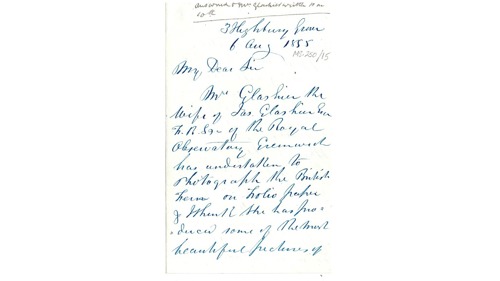

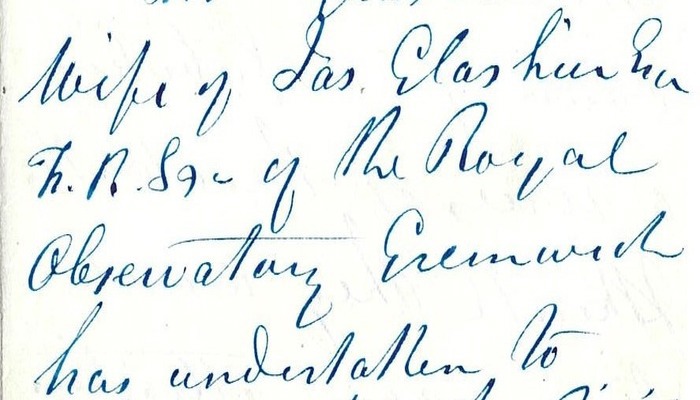

MS250.15.1 Letter from JT Bauerbank to William Church informing him that Mrs. Glaisher the wife of James Glaisher of the Royal Observatory, Greenwich has undertaken to photograph the British fern.

Reading 19th century documents

I spent 100 hours with the Glasgow Photographic Association Collection, which is kept in Special Collections at the Mitchell Library. Here's what I learned:

Starting to dive into the documents of any collection can be quite a daunting task, but with a little knowledge of your subject matter and this guide to reading cursive in the 1800s, you should have no problem! In the 1800s, and in our documents surveyed specifically in the Glasgow Photographic Association, two main styles of handwriting can be observed: the Copperplate or Round style and the Italic style.

Copperplate was often used for business documents, as it was neater and easier to read later on. Many letters leaned more toward the slanted, slightly messier, Italic style, which allowed the writer to scribble more quickly. Copperplate is most similar to modern handwriting, especially modern cursive, and most Copperplate documents are readable by anyone who knows their cursive. Italic, however, is a bit harder to read.

One must also factor in that any one writer will have their own personal style in handwriting, regardless of whether they are writing in the Italic or Copperplate style. Here are a few tips on how to read even the most illegible letters:

Anne's top tips for reading letters

Become familiar with modern cursive.

A strong understanding of modern cursive and the shapes of cursive letters is extremely important for reading both Copperplate and Italic, as many of the shapes have carried over to modern handwriting. You don’t have to be proficient in cursive and write in it per se, but it will help.

Try to read your document first.

Some documents can look quite scary at first but if you give it a good try, it may be easier than it seems. When you are reading, write down what the document seems to be about and any parts of the document you are having a hard time reading. If you’re having a very hard time reading your document, there are also a chance that it is in a language you are unfamiliar with, which is why it is imperative that you try to read your document before breaking it down word by word.

Write as you read.

It can be hard to keep track of the words you have read when your brain is trying very hard to process the words in front of you. Writing down the words you have already read also allows you to return to the text for context clues if you are having trouble with words later on.

Notice patterns in the handwriting.

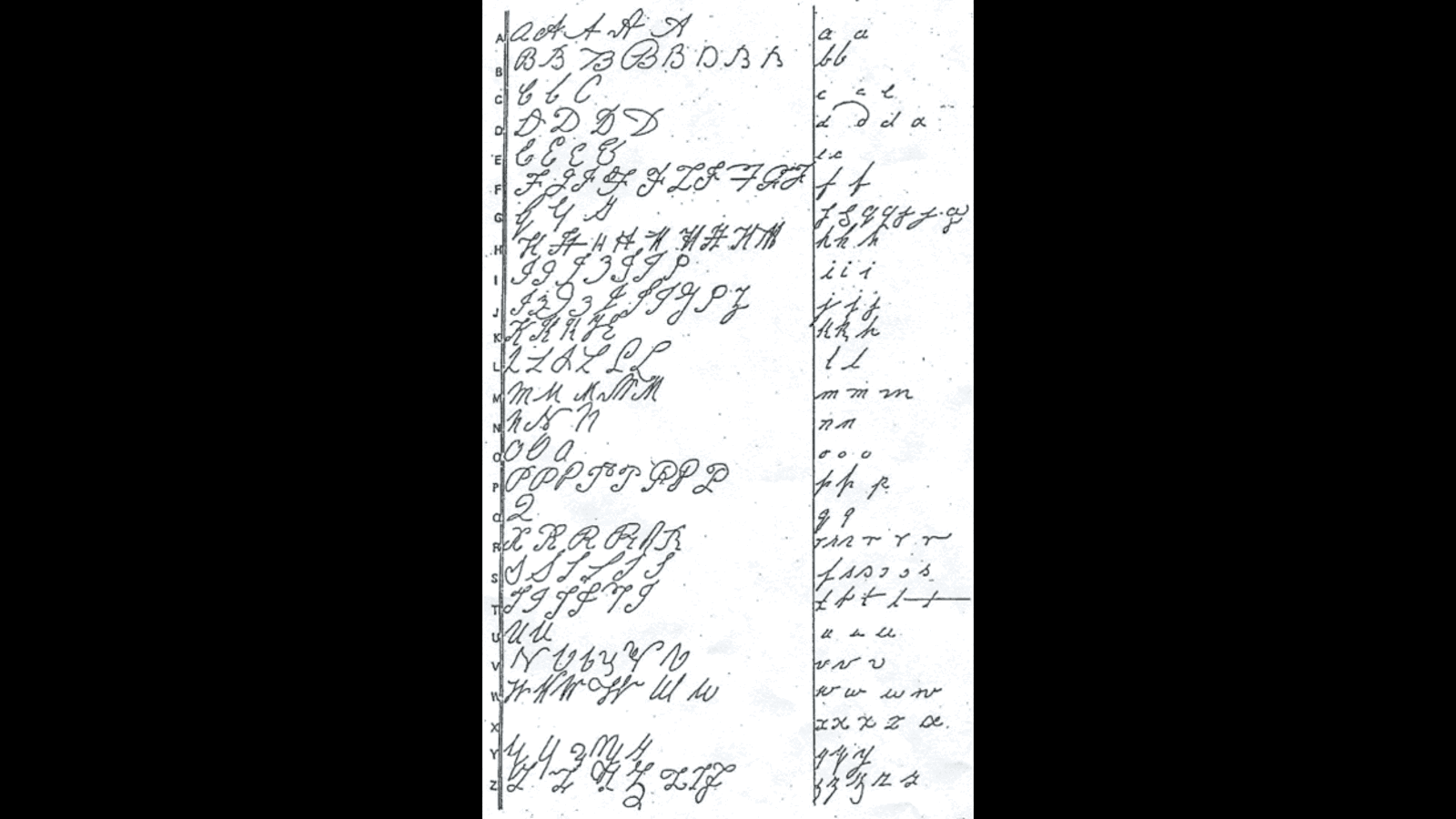

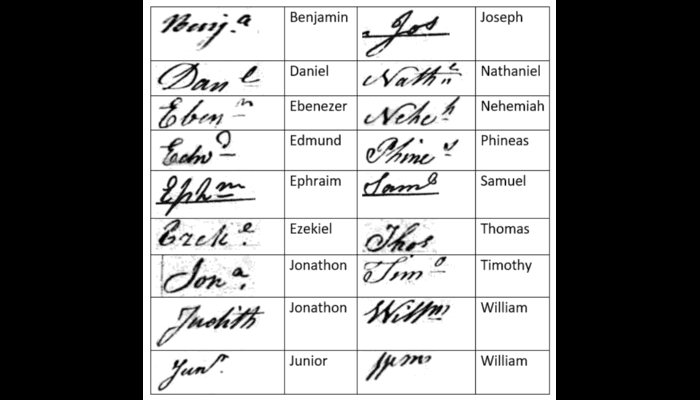

When you figure out what a word is in a document that is hard to read, examine the word and the shapes of the letters in it. Often, when writing cursive, these shapes are often the same throughout the document, which can help you when reading a tough word. It is helpful to use this guide below for examples of common ways to write each letter. While it is from Pennsylvania in 1800, it is very useful in looking at documents in the UK and across the world throughout the 19th century.

Write the word out yourself.

If you are having trouble reading a specific word, draw out the shapes of the letter. This may make a connection in your brain and allow you to figure out what the word is.

Make room for human error.

It is important to remember that the person who wrote the document you are looking at was not perfect - they made spelling errors too! If a word is making no sense and seems like gibberish, try to think of the closest word to it, it may be a spelling error. It helps sometimes to type your gibberish into Google and let it correct you, it may know what the word is, or perhaps it is a new word to you entirely!

Educate yourself on the terms of the time.

For example, if you are researching early photography, the term daguerreotype may appear. In some of our documents, this looks like the letter d and a very long

scribble, but is actually the word daguerreotype, an early photography process. Without becoming familiar with key terms for your subject and time period, you may be missing a large part of the puzzle!

Become familiar with 1800s cursive letter shapes and abbreviations.

Here are a few tricky shapes and abbreviations used in the 1800s.

Tricky shapes and abbreviations

Tricky shapes and abbreviations

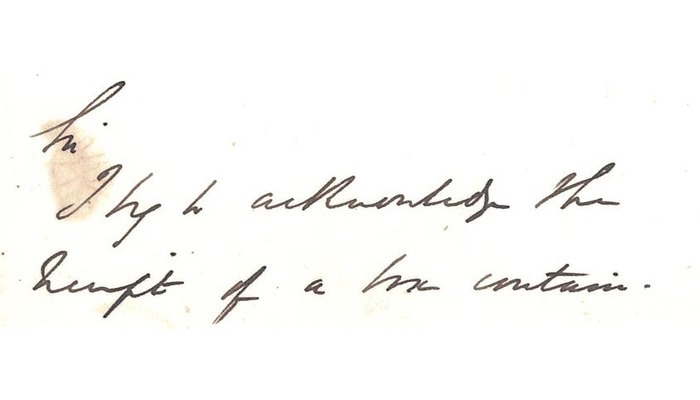

"Crossing the t and dotting the i"

Sometimes writers do not bring the cross stroke in a capital H all the way across, making the H look like a capital s and a t.

Additionally, sometimes dots are not directly above the i, but rather, are far off to the side.

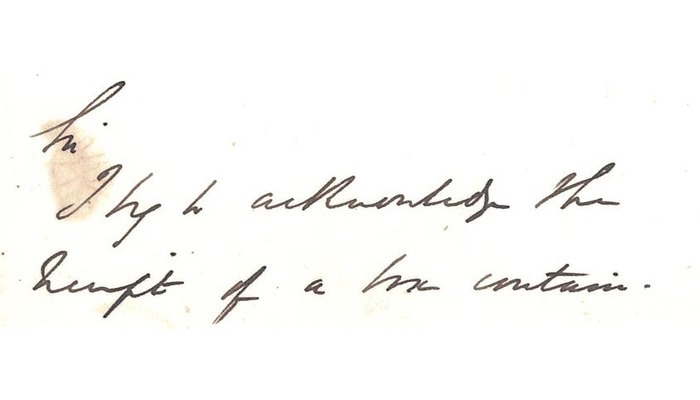

See above (top left) for image of MS250.1. "Sir, I beg to acknowledge the receipt of a box."

The double or long s

When two of the letter s are next to each other, in the 1800s, it was common practice to have the first s be longer than the other. This often made the first s look like an f or p.

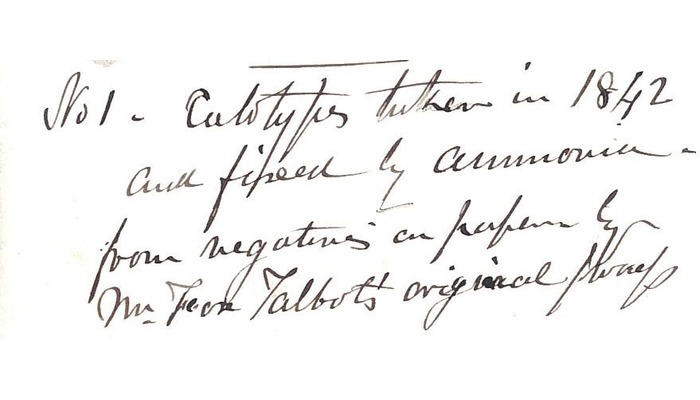

See above (top centre) for image of MS250.2 "No 1 - Calotypes taken in 1842 and fixed by ammonia from negatives on paper by Mr Fox Talbot's original process."

Round letters are flat

The Italic style was often written in a rushed, slanted way, which made rounder letters like ‘e’, ‘a’, ‘o’, and others look squished or flat.

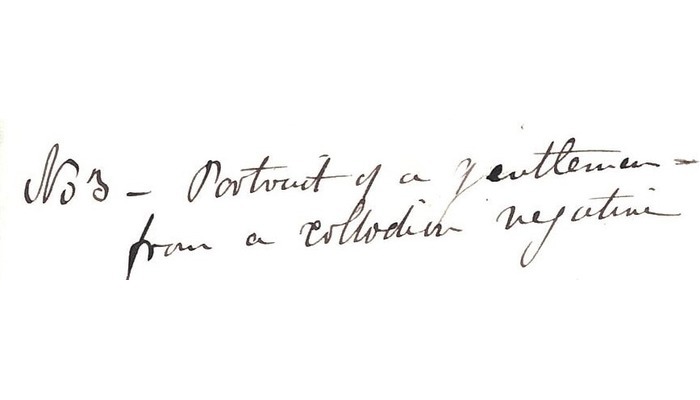

See above (top right) for image of MS250.2 "No 3 - Portrait of a gentleman from a collodion negative."

The ‘limp’ R

This looks like a very large lower case n but may be an R

Missing cross strokes

With time, the lighter strokes of ink may have faded. These lighter strokes are often cross strokes (such as when you cross your Ts) and dots above the i. It is important to remember that these cross strokes and dots may be missing when trying to discern what a

word is.

See above (bottom left) for image of MS250.15.1 Wife of Jas. Glashier has undertaken to..." - note that there is no cross on the t of "undertaken".

Name and position abbreviations

Very common names were often written as the first few letters of the name followed by one letter written much smaller next to it. For example, William was shortened to a capital W and a small m, and James to Jas.

Job positions were also shortened, such as Sec with a small y.

See above (bottom left) for image of MS250.15.1 Wife of Jas. Glashier has undertaken to..."

Find out more

We hope this guide has been a helpful start for reading cursive of the 1800s, and that you can fully immerse yourself in the collections of the Mitchell Library.

About the author

Anne Van Hoose is a fourth year Digital Media and Information Studies student at University of Glasgow. She is also a graphic designer, and used to give tours at the Hunterian Museum. Her interests include true crime, making board games, and baking. She spent her 2024 summer volunteering with the Mitchell Library, and hopes that you will spend some of your free time volunteering with your local galleries, libraries, archives, and museums!